Artists, critics, and academics insist that the defining factor for any object or action to be art is intent. Even in a postmodern mindset where anything—any act, any work of cultural production, or any object (any thing)—can be art, what makes that thing art is the intent that it is art. This, of course, is rooted in the Modernist ideology of authority.

Modern thought places the utmost importance in authority, because it is through authoritative figures, statements, and processes that we can determine Truth. And capital-T “Truth” is the utmost authority. For this purpose, fields of study are singled out and highly educated experts spend their time investigating and advancing their knowledge of these fields, producing work that is True Science or True Music or True Art. By designating himself as an Artist, a person then declares his intent to make art. From then on, what he decides is art—what he intends art to be—is just that. His justification is manifest in his position as an Authority on Art, an authority granted by specialization and expertise.

In the period of High Modernism (namely, the movements of Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism), the intent of being art was enough justification for a thing to be art. During the Postmodern period, however, simply being art was not enough justification for an object. Beginning in the late 1960s, art gained (or re-gained) the requirement of meaning. In order to have impact, the work needed to do more than just be art, it needed to mean something.

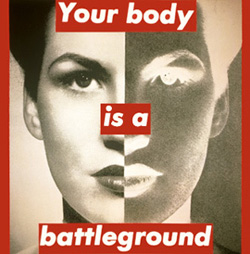

In some circles, this “meaning something” depended on shock—a tool inherited from early Modernist painters who seemed intent on forcing the advancement of society, which was another topic of Modernist importance. High Modernists like Picasso and Pollock aimed their shock inward—the shock of non-representational painting pushing art to a more advanced, more specialized place. However, like Realist painters such as Manet, Postmodern artists like Barbara Kruger and Ed Kienholtz aimed their shock outward, putting society itself in the crosshairs.

Activist artists like Judy Chicago, Mel Chin, Guillermo Gomez-Peña, and Sue Coe made artwork with dual intent: to be art and to disrupt. The requirement for rupture seems to have become inherent, especially in art produced and justified in an academic setting. Disruption may not always be readily apparent, and thus artist’s statements emerge as a way to explain what is disruptive about a particular work or a particular artists’ oeuvre.

What is peculiar about the supremacy of rupture as a requirement of art is that the intent of rupture seems to have the capability of being granted after the fact. Artists who do not intend to their work to be disruptive in the present to be dismissed, and artists who created rupture in the past, whether or not they set out to do so, are elevated. A reader commented on my last post (Thomas Kincade is Dead. Long Live Thomas Kincade) on Facebook, arguing against my comparison of Kincade to Andy Warhol:

Even if he claims that he did not intend to, Warhol’s imagery (as banal as it was) at the time forced an examination of the boundaries of art (rupture). That’s pioneering. Kinkade’s imagery (although his methods of production and commercialism could be argued as similar to Warhol’s) does not hold the same power of rupture, just based on content alone.

Warhol was famously non-committal about his intentions regarding meaning in his work. He made works with a popular appeal in a businesslike way that seemed to challenge the accepted specialized, reified nature of art. Critics, history books, and hero-worship have assigned the intent of rupture to Warhol, not Warhol himself. If intent is all important in the status of an artist, is assigned intent just as powerful as declared intent?

It appears that this is the case. The reader concluded her comments by writing, “I believe Kinkade’s illuminated cottage scenes are more along the lines of an allopathic art—an easy sell.” Kincade was about business and selling, and Warhol was about critiquing the art world and/or society. However, Warhol’s own statement on the matter was that “Being good at business is the most fascinating kind of art.”

The figure of Andy Warhol has been ascribed the role of sly critic of mass consumer culture and big-money art markets even with the facts and trappings of his fame and wealth readily apparent. A similar statement can be made about the work and person that is Jeff Koons. My favorite statement regarding Koons comes from Robert Hughes, “If cheap cookie jars could become treasures in the 1980s, then how much more the work of the very egregious Jeff Koons, a former bond trader, whose ambitions took him right through kitsch and out the other side into a vulgarity so syrupy, gross, and numbing, that collectors felt challenged by it.”

Hughes goes on to say, and I agree, that you will be hard-pressed to find anyone in the art world who claims to actually like Koons’ work. But because it is ultra-kitsch and still presented as art, we assume the intent is to critique the vulgarity and simplicity of consumer or of the art market itself. Koons is a businessman, and a shrewd one at that. He makes a lot of money by “challenging” collectors while stating directly that he is not intending to critique or challenge art, beauty, or kitsch.

Of course, he is challenging them. It is not his stated intent that is accepted as fact, but it is the intent we as viewers and critics have assigned to him. In a postmodern view, the authority has shifted to the reader, to the viewer—to the end consumer of a cultural product. We are no longer interested in a Truth of art, but instead we accept the personal truths of our own subjective views. Saying you didn’t intent to go over the speed limit does not mean you didn’t do it, and Jeff Koons, Andy Warhol, or even Thomas Kincade saying they don’t intend to create disruptive art work doesn’t mean they aren’t doing it.

If rupture is the new defining characteristic of art, then intent no longer can be. A child doesn’t intent to disrupt a funeral, but it will because it wants attention. Attention is the intent, but rupture occurs nonetheless. Kincade just wanted attention and fame, but that shouldn’t stop us from viewing the work as a disruptive critique of the market. It hasn’t stopped us from doing the same with Warhol.

The reader’s comment used the word “allopathic.” Allopathic, according to Merriam-Webster online, is “relating to or being a system of medicine that aims to combat disease by using remedies (as drugs or surgery) which produce effects that are different from or incompatible with those of the disease being treated.” In this case, the system of art critique is allopathic. Typically, critique is aimed at works of art that intend to be art in a certain way. Here, we are critiquing work in a way different or incompatible with its supposed intentions when being produce. In a world of relative truths, that doesn’t make the critique any less valid.

The Nostalgia of 9/11

9 09 2011Here we are nearing the middle of September, a time when, once again, we start to see a buildup in cultural production—television programming, radio interviews, news commentary, etc.—centered around the topic of remembering the attacks on the World Trade Center towers and the Pentagon on September 11, 2001. This year, marking the tenth anniversary of the event, has the familiar commemorative speeches, memorial services and monument dedications that we have come to expect.

The further away we get from the date of those attacks, and the more memorializing that happens concerning them, the less impact the events seem to have. The iconic images are, by now, quite familiar—the video shots of planes hitting the towers, the collapse of each, almost in slow motion, the people fleeing from the onrushing cloud of dust and debris, the thousands walking across the Brooklyn Bridge, the photo of the firemen raising a flag on a damaged and twisted flagpole. The repetition of those images, especially over time, begins to obscure our own personal memories, our own personal experiences, of that day.

Jean Baudrillard argues that the attacks, to most of the world, were in fact a non-event. I was living in Spokane, Washington, nowhere near New York City, Pennsylvania, or the Pentagon. My experience of that day was through the images, not in the events themselves. The attacks did not really happen to me. But in a hyperreal world, “factual” experience isn’t the end of the story. While the physical attacks had no bearing on my experience, the symbol of the attacks did. The images that were repeated over and over again that day, and in the weeks and months that followed, on television, radio (if you’ll remember, all radio stations switched to whatever news-format they were affiliated with for about a week), and the internet. The images were re-born in conversations between friends, family, and acquaintances. The violence did not happen to us, but the symbol of violence did. As Baudrillard states, “Only symbolic violence is generative of singularity.” Rather than having a pluralistic existence—each person with their own experience and understanding of any given topic—our collective experience is now singular. Nine-eleven didn’t physically happen to me, so it’s not real, but it is real. It’s more real than real. It’s hyper-real.

But in the ten years since, the hyperreality of the attacks seems to be fading into something else. As the vicarious (for most of us) experience fades into memory, the singularity of that symbolic violence is shifting into one of nostalgia. The events as historic fact are replaced by our contemporary ideas about that history as it reflects our own time. Nostalgia films of, say, the 1950s aren’t about the ‘50s. They are about how we view the ‘50s from 2011.

The 1950s scenes in Back to the Future don't show us the 1950s. They show us the 1950s as seen from the 1980s.

We’ve seen this nostalgia as early as the 2008 Presidential campaign, which included many candidates using the shorthand for the attacks (“Nine-eleven”) to invoke the sense of urgency or unity or the collective shock of that day. The term “nine-eleven” no longer just refers to the day and attacks, but to everything that went with them and to the two resulting wars and nearly ten years of erosion of civil liberties. What happens with this nostalgia is that details become muted and forgotten, and we end up molding whatever we are waxing nostalgic about into something we want to see—to a story we can understand and wrap our heads around.

This morning I listened to a radio interview of a man who carried a woman bound to a wheelchair down some 68 floors of one of the towers on the day of the attacks. He was labeled a hero, but in subsequent years, slid into survivor’s (or hero’s) guilt and general cynicism. He looked around the United States in the years after the attacks and saw the petty strife, the cultural fixation on celebrity trivialities, and the partisan political divide seemingly splitting the country in two. He longed for the America of the time immediately following the attacks, “Where we treated each other like neighbors,” the kind of attitude, as suggested by the interviewer, that led him to offer to help this woman he did not know in the first place.

Certainly, there was the appearance of national unity after the attacks. Signs hung from freeway overpasses expressing sympathy for those in New York. Flags hung outside every house in sight. People waited for hours to donate blood on September 12, just to try to do something to help. The symbols of unity were abundant, but division abounded as well. Many were still angry, skeptical, and suspicious of George W. Bush, who had been granted the presidency by a Supreme Court decision which, to some, bordered on illegal. Within communities, fear and paranoia led to brutal attacks on Muslim (and presumed-Muslim) citizens. Fear led to post offices and federal buildings blockaded from city traffic. In Boise, a haz-mat team was called due to suspicious white dust, feared to be anthrax, on the steps of the post office. It turned out to be flour placed there to help direct a local running club on their course. The flags were still flying, but the supposed sense of unity and “neighborhood” was, in actuality, suspicion.

To look back at September 11th, 2001 and view it as a time of unity in comparison to the contemporary political divide is nostalgia. The view is not of the historical time period, but what one wants that time period to have been that then acts as an example of what the present “should” be. Perhaps nostalgia is inevitable. As time passes and memories fade, the repeated symbols of any given time or event become re-purposed, gain new meaning from the reality (or hyperreality) from which they are being viewed. The goal for many regarding the attacks is to “never forget.” The repetition of the images keeps us from forgetting, but it also contributes to the memory changing.

Sources: Baudrillard, Jean. “The Gift of Death.” originally published in Le Monde, Nov. 3, 2001

Here and Now (radio show). “A Reluctant 9/11 Hero Looks Back.” Airdate: Sept. 9, 2011

Share this:

Comments : Leave a Comment »

Tags: 9/11, contemporary culture, hyperreality, Jean Baudrillard, meaning, memory, nostalgia, postmodern theory, September 11th, World Trade Centers

Categories : Culture, News Commentary, Our Postmodern Reality