While my writing for this blog has waned over the last few months, I have taken up working with another exciting group of writers at Latitude. Latitude is an unflinching look at global news and opinion from a Spokane perspective. This particular entry could easily be something I wrote for Contemporary Critique. Take a look, and take a look at the other exciting and powerful young writers at Latitude.

The Work of Art Work

24 11 2012Comments : Leave a Comment »

Tags: art, contemporary culture, Culture Wars, public arts funding, Spokane Symphony, Spokane Symphony Strike, the business of art

Categories : Art, Arts Organizing

Influence

26 08 2012In the Fall of 2007, I was new to organizing slams. One night, I arrived at our usual venue early to set up, only to find that the venue (a comedy club that was usually dark on Mondays) had booked an X-rated Hypnotist on our usual day. I was somewhat disappointed, but I resigned the slam to what I saw as its fate for the evening: I assumed we’d have to cancel. When I called the Boise slam-master, Cheryl Maddalena, to tell her the news, she did not hesitate in telling me that there was no way we were cancelling. “Aren’t there restaurants and other clubs right around there? Go ask them if we can have the slam there?”

It seemed preposterous, but it happened. We walked across the street and asked the wait staff at a restaurant and bar if we could hold a one-night event in their space… you know… right now. Surprisingly, they agreed and we were back in business. Never mind that most of the audience was there to eat dinner, not see a slam. Never mind that a majority of the poets who performed had prepared satirical baby-eating poems, and were now performing them for old ladies trying to eat fish and chips. This is not the most awkward situation in which I have performed poetry, nor is it the only one to involve Cheryl Maddalena. In fact, all of them involve her.

We once performed during registration day at the College of Southern Idaho. The school put us right next to the doors of the registrar’s office and across the path from the LDS student organization. A group of Boise poets once performed for the city on the sidewalk in front of a parked bus. The city did not provide us with a PA system or with signage informing passersby why four earnest young people were shouting metaphors at them as they passed. Maddalena and three other poets were dismissed from the second half of a scheduled workshop and performance by a high school for using the word “dildo” in a poem. Maddalena had made it a point to clear the content with the school beforehand. Apparently, it was not sufficient.

Cheryl Maddalena, Isaac Grambo, and Tara Brenner perform “Moustache Poem” at the Individual World Poetry Slam Championships (iWPS), Berkeley, CA, 2009

Boise poets have performed at everything from car washes to wine tastings to high-school punk concerts to burlesque shows. It isn’t always pretty, but it’s always done with a purpose, and it’s always done with heart—and that heart is embodied in the person of Cheryl Maddalena.

Cheryl Maddalena did not invent slam poetry, nor did she bring it to Boise, Idaho. Maddalena started slamming in Berkeley, California while she was earning her doctorate in psychology. In short order, she was on teams competing in for National Poetry Slam Championships. I don’t mean that she was just at Nationals, I mean she was on the Finals stage.

Jeanne Huff and Bob Neal started a slam in Boise in 2001. As scenes often do, the scene was in a state of flux when Maddalena moved there in 2005. Some of the novelty had waned, the regular poets were growing out of slam and moving on to other things, and the organization had never been the kind of tightly-run ship that one would see in a slam venue in Berkeley, Seattle, or Chicago.

Cheryl Maddalena is, quite often, the most reluctant organizer I know. She didn’t want to assert control over Big Tree Arts, Inc. (the non-profit that organizes slams in Boise). However, she couldn’t bear the idea that a scene wouldn’t send a team to Nationals, or that poets wouldn’t have a way to raise funds to make trips they might not otherwise make, or to not see the kinds of poets she had come to know and love from the Bay Area, New York, Vancouver, and all points in between. There are times when arts organizing hurts feelings and breaks friendships, and the growing pains of Big Tree Arts left a few former figures of poetry in Boise by the wayside. This is an unfortunate byproduct of making changes and moving forward, but for any kind of scene—be it slam or visual art, concert venues or literary bongo-circles—changes will ruffle feathers. Old people will leave, new people will enter. The most important part is the art, and that is what must be maintained as a constant.

Sometimes meeting someone who will influence your life is a rather inauspicious occasion. When I first saw Maddalena perform, I leaned over to a friend who had come to the slam with me and said, “If I EVER sound like her, you have to tell me and I’ll walk away from this whole slam poetry thing immediately.” At that moment, I had no idea how much she would eventually teach me about performing, organizing, and the inherent value of being an artist.

For all of the crazy things Boise poets have done, Maddalena has been a leading voice insisting the poets be paid in some form or another. Poets are afforded the chance to work as volunteers for Big Tree Arts in exchange for BTA covering the bill to send them to Nationals, iWPS, or WOWPS. Poets from out of town who lead workshops are paid $150. At a time when I was altruistically clinging to an idea that art was priceless, Maddalena was teaching me that even that has a price. Poets who want to live as poets need to be paid to do so.

Cheryl Maddalena taught me the importance of the audience and how the seemingly arbitrary rules of slam are the key to audience participation. In some cases, I resisted the lesson, telling her “I will swear at any place at any time—these eight year-olds are are going to hear these words on the playground eventually!” In some cases, it was a lesson she let me learn on my own, sacrificing her own ego by performing “White Lady,” a poem I had insisted on, in a room full of Black poets and people waiting for a Hip-Hop concert to start.

That performance of “White Lady” didn’t turn out like this, but from the dirty looks and the low scores, it may as well have.

I am influenced by artists long dead and by writers so famous I will never meet them in real life. I am also influenced, on a much greater and personal level, by artists, writers, and organizers I work with every day who don’t have book deals and will never show up in an Art History survey course. If I’m being honest with myself, I have to admit that Cheryl is the second-greatest influence on me and my work, next to my own father. If this essay reads like a eulogy, let me be clear: Cheryl Maddalena is still very much alive. She continues to write, organize, and perform and has the unique ability to both inspire and frustrate me, even when I’m eight months and 500 miles removed from Boise.

In some ways, Maddalena is a reluctant organizer and, in others, she is a selfish one. She keeps organizing slams, writing grants, coaching troupes of younger, less experienced poets to perform in front of audiences as foreign to native Boiseans as performing for Martians, and writing, writing, writing. She keeps organizing because she can’t bear the idea of slam not being there for her. Luckily for me and for the rest of Boise, keeping it around for herself has kept it around for us as well.

Comments : Leave a Comment »

Tags: arts organizing, Benjamin Lzicar, Big Tree Arts, Boise, Cheryl Maddalena, slam poetry

Categories : Arts Organizing, Poetry

Failure is Always an Option

15 07 2012I stole this slogan from Mythbusters, and it applies to pretty much the entirety of life, not just science and not just art. Sometimes, the best plans and the most professional presentation you can muster just aren’t enough. Nobody shows up to your event. Your artwork does not sell. A judge gives you a 1.3 for your poem. 1.3! That happened to me once. The fact that failure is a possibility should not dissuade you from attempting something. Nobody ever did anything truly great without the very real possibility of falling flat on their face.

On a small scale, this applies to making changes to a given artwork. If you are working on a drawing and don’t want to make a needed change because you are afraid that you might mess up the whole thing, the whole drawing will suffer as a result. Poems that you can’t bear to edit even though they are too long or don’t communicate your idea clearly won’t do anything but stay mediocre unless you do something to change it.

Great artists take risks and great artists fail. It’s a fact of progress, and there’s no use being afraid of it. In my experience the anticipation of failure is more gut-wrenching than the failure itself.

Of course, sometimes failures scuttle careers. In April, I wrote a blog entry about how Daniel Tosh is Important. I argued that his satire is more cutting and critical than the dick-jokes and racism it seems to be perpetuating, and I stand by what I wrote. Tosh now finds himself on the wrong end of the ire of many, especially feminists, after responding to a heckler during a comedy show with a “joke” about the heckler being gang-raped.

From what I understand of the incident, Tosh had been making a point about how there are terrible things in the world, but that doesn’t mean nobody should make jokes about them. When the woman called out that “rape jokes are never funny,” he responded in a satirical attempt to exaggerate his own stance by cracking that it would be funny if she were raped by five members of the audience right then and there.

His response was a failure. It did not effectively satirize mindless rape jokes, nor did it satirize knee-jerk indignation regarding humor with violence as its genesis. Because this one response failed, the entirety of Tosh’s body of work comes into question—is he really just as bad as the horrible “comics” who respond to the Tosh.0 blog posts?

A similar thing happened to Michael Richards in 2006 and public opinion of him still hasn’t recovered. In 2011, I posted a vitriolic critique of university art education on Facebook. I am no longer a professor.

My purpose is to illustrate that even big-time celebrities fail. Whether I defend or vilify Daniel Tosh, he is still important. What more are we seeking as artists? Whatever the risks you may take as an artist, the fear of failure shouldn’t stop you from taking them. Public opinion is something to pay attention to and try to manage as a professional artist, but to attempt to cater to it is not the answer. After all, if what you’re saying doesn’t make your voice shake, is it really worth saying?

For a response to the Daniel Tosh incident, please read this remarkable post by Lindy West: How to Make a Rape Joke.

Comments : Leave a Comment »

Tags: art, Daniel Tosh, failure, rape, rape jokes, success

Categories : Art, Art and Meaning, Culture

Presentation is Everything

15 07 2012While I spend a great deal of time and effort in this blog proclaiming the values of thinking about art as an integral part of everyday life, I am well aware that the products of art are commodities and if a person is going to live an “everyday life” as an artist, that person is going to need to have some level of monetary success result from those commodities. Like anything else, art has real, monetary value—despite the notion that works of art are “priceless.”

However, artists trained in the Modernist mindset to make art for art’s sake inevitably have some level of resistance to looking at art as a business. Like the relationship between art and society, each decision that an artist makes about his art—how to create it, how to display it, and how to (or not to) profit from it—is also the artwork.

I have written about the danger in thinking about art as something that exists outside of society. In doing so, we are thinking about art as something that is not essential, trivial, and easy to marginalize. If we expect to make our living as artists, we need to present what we do as something that is both necessary and of monetary value. Nobody questions Apple for charging money for iPods. It has presented the product to us as a valuable and necessary part of our lives, and we are prepared to pay handily for it.

Charge money for your art. In The Dark Knight, the Joker says something to the effect of, “If you’re good at something, never do it for free.” Don’t give away your artwork, don’t hold events that ask for nothing at the door. Your work is important and the person who is consuming it should be prepared to compensate you for your time, effort, and skill.

Of course, market forces apply here. You may not be able to charge $1.5 million for a painting just because you feel like it’s worth that. A poet’s chapbook is not going to sell for much more than five dollars, and you won’t be able to charge $45 at the door for a rock show in a dive bar unless your name is Mick Jagger. But $5 is $5, and art patrons need to get used to the idea that art is something that costs real money so it doesn’t seem so ridiculous to have their tax dollars go to the NEA to support artists.

The road goes both ways. As an artist, spend money on art. Pony up the $5 to see your friend’s open mic performance, even if they say they’ll get you in for free. Put a couple bucks in the donation jar as it’s passed around, even if you’re performing and trying to win some of that money back at a slam. Buy (don’t trade) the work of other artists; even your friends, even if it’s expensive. This is how economies work. If cash isn’t circulating, it isn’t doing anybody any good.

If you are charging money for an artwork or for an event, present it like it is worth money. Hang your artwork properly. Make sure it is lit well, that the wall is relatively blemish-free, that the painting is dry (even though people aren’t supposed to touch the art, they touch the art—don’t give away souveniers of paint on fingers). If you are producing a performance event, make sure your PA system is set up and working before the doors open, have the chairs arranged how you want them… START THE EVENT ON TIME. If you want people to value your work, you should value their time. Respect your audience.

Patrons aren’t the only people involved in an art event. There are also other artists, venue owners, and journalists if you’re lucky. Treat these people with respect as well. Buy a drink from the bar. If the bartender buys it for you, leave the bartender a tip. Look at and discuss the work with the other artists in your exhibition. Stay for and listen to other performers in your event, even if you go first. Especially if you go first. If you are a performer, leaving a concert, open mic, poetry slam, or play in which you are involved before it is over is the height of rudeness. (Of course there are exceptions, but at the very least you should explain why you are leaving to an organizer and apologize—even if you don’t mean it).

Steve Buscemi’s character is the only one who maintains professionalism in Reservoir Dogs. He’s also the only one who makes it out alive.

By making a livelihood out of being an artist, you are positioning yourself as a professional. Act like one. Professionals don’t have to be boring, they don’t have to be stuffy, they don’t have to be snobs and wear cravats. A professional conducts himself with the same respect for others that he expects from them.

Comments : 2 Comments »

Tags: art, art and money, contemporary culture, professionalism, success

Categories : Art

Villains

24 06 2012I am a regular patron of Broken Mic, a performance poetry open mic in Spokane, Washington. The average age of both audience and performers is somewhere in the late teens and early twenties. There’s a lot of angst, altruism, and shock value and even more support from poets and the audience. That support is not, however, unconditional. In April, a poet stood in front of the audience for the first time ever, and prefaced his poem by saying, “I wrote this poem about butt sex and I’m going to do it even if there are little kids here, so fuck you.” By the time he was finished, he was hearing boos as he went back to his seat.

The content of the poem didn’t bother me. Shock and vulgarity are used in many instances to gain attention. While I think his poem lacked in the category of substance, writing about something that is culturally taboo and performing it in an atmosphere that promotes free speech shouldn’t be a problem. The fact that there was a six or seven year old child in the front row doesn’t bother me, either. The mother was present, there is an announcement at the beginning of every event making it clear that poets can and will say things that offend. If she had wanted her son to not be present for this display, she could have left well before the offending poet made it to the microphone.

Where the poet erred was in alienating the audience. Leading off by telling the audience to go fuck itself put the performer at odds with them before they even knew who he was or what he was all about. American audiences hold self-assured artists in high regard, but not before they’ve either paid their penitence or demonstrated their work as being of the highest quality. We may delight in the character of the villain, but we always expect the good guy to win in the end.

LeBron James alienated a nation of basketball fans in 2010 by leaving the Cleveland Cavaliers for the Miami Heat. He compounded the alienation by announcing his decision in an hour-long televised special, the team holding a celebratory pep rally before the newly-formed group had even held one practice, and James telling the crowd that they would win “not two, not three, not four…” but eight championships. Cleveland fans burned his jersey in the streets. The rest of the basketball world decried this hubris, and LeBron, for the first time in his life, found himself cast as the villain.

James and the rest of the team embraced this role as they pursued a championship in the 2010-2011 season. While American audiences take a certain pleasure in villainous characters like Frank Costello in The Departed or The Undertaker in professional wrestling, they have little sympathy for a villain who has not accomplished anything. LeBron, who had come straight into the NBA out of a ridiculously-hyped high school career, had never received any kind of disapproval, certainly nothing on this scale with this kind of vehemence. The villain role was not something James and the Heat could fill, and their loss to Dallas in the 2011 NBA Finals was the equivalent to getting booed off the stage after an indignant poem about anal sex.

LeBron alienated the public by very visibly and very publicly demonstrating that he did not care what they thought. Of course, he did care, and was genuinely hurt when the public reprimanded him for his actions. Whether he wanted to admit it or not, the poet from Broken Mic in April was hurt by the boos as well. At the heart of the actions of both was a fear of rejection, which was all but guaranteed.

If a kid wants to protect himself form schoolyard mockery, one tactic is to display that he does not care what the mocking children think. If they get no response, the mocking is fruitless and they move on. If a performer is putting herself in front of an audience with the danger of not being approved, she can mitigate the rejection by claiming to not want the approval in the first place. Superficially at least, both sides come away as if they’ve won. The audience has rejected the performer for hubris, and the performer has rejected the audience’s lack of approval by saying she was never seeking it. “Of course they didn’t get it. They’re just too simple to understand…”

We can compare this attitude to the Greenbergian notion of the separation of high Art from the rest of life. For Greenberg, if Art was to progress and advance, it needed to be separate from the rest of society—artists should not worry about the approval of the masses. Non-educated art patrons and popular audiences were to be ignored in favor of focused investigation into the specific area that was High Art. A painting did not exist for the enjoyment of some schmo on the street—it existed for the sole purpose of being a painting.

The authority embodied in the artist (here, Jackson Pollock) and the critic (in this case, Greenberg) made the hubris of High Modernism titanic. In a postmodern age of skepticism, authority isn’t what it once was.

On the one hand, this alienates the larger public. On the other hand, it provides a group for artists to identify with. There is a cachet that comes with being an insider—whether it’s in a dance-club scene, the world of high art, or poets in Spokane. The attitude paradoxically justifies whoever holds it as both an individual (in rejecting the expectations of “the masses”) and a part of a group of artists, writers, performers, or thinkers who hold similar attitudes, education, and experiences. The attitude of specialization inherently creates cliques, and if we remember anything from Junior High School, cliques get jealous of other cliques.

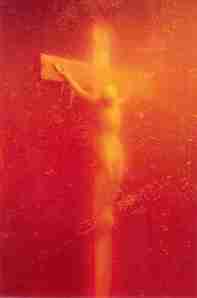

In 1989, Piss Christ, a photo by Andres Serrano, became the flashpoint in what would come to be known as the Culture Wars. Without simplifying the issue too much, the photo was given an award that was funded partly with money from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). This enraged conservatives who used the image and the award as reasoning to cut funding to the NEA.

The fact that it was a photo escaped some politicians. The fact that it was among a series of other photos of different objects and figurines submerged in a mixture of urine and cow’s blood escaped almost everybody. The formal or conceptual considerations of Serrano were moot points in the larger discussion—the shock was all that mattered. It was an inflammatory image with an inflammatory title. This, combined with the already entrenched attitude of the art elite dismissing the approval of wider audiences, meant little sympathy and little resistance to the evisceration of the NEA’s funding of the visual arts.

In 2012, the political climate again has public funding for the visual arts on the ropes. In Spokane, there is much hand-wringing over the fate of the Spokane Arts Commission, which has already seen a long series of cuts which has left it a shell of a “commission” with only one employee and a handful of volunteers. The Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture (known as the MAC) has fired its director for undisclosed reasons and is facing the ire of the public for this decision and a demand for an explanation. The MAC has also been forced to look for private sources of funding as public money for visual art in the region has dried up.

Outside of the people actively involved in the arts in Spokane (which consists in no small part of artists themselves), there has been little protest over the possibility of doing away with the Spokane Arts Commission. The Commission oversees the acquisition and maintenance of public art projects in the city from the Harold Balazs sculptures floating in the river to the garbage-eating goat to the murals on railway underpasses. It is an organizational hub for small non-profits from Saranac Art Projects to Et. Al. Poets, and, yes, it helps those organizations find, apply for, and get government grants.

The Spokane Arts Commission is on the precipice of nonexistence not because of anything it does, but because of an attitude perpetuated by those involved in High Art. We ignore mass audiences at our own peril. By continuing to isolate ourselves and dismiss the larger public, we make what we do appear to be something other than necessary. What’s worse, the expectation of government funding has led to ignoring potential customers. If we do not expect them to pay to see what we have to offer in person, how can we expect them to think it is necessary to pay via taxes if they don’t (or aren’t even invited to) see it?

The problem isn’t with the product: poetry, art, music, and plays are as vibrant in Spokane now as they have ever been. The problem is in perception—it’s in marketing; it’s in public relations. If we abandon the idea that art should be separate from the rest of life, those people who decide how art is funded and therefore how artists can live will see it as a necessary part of life. This change in attitude starts with the artists and performers. It starts with conversations. It starts with including anyone who is even remotely interested and alienating no one—even if what you are saying with your work is confrontational.

With inclusivity, art can be a valued part of everyday life, and everyday life can be a valued part of art. We aren’t going to force anyone to pay attention to our work by telling them we don’t care what they think. We have to care. Without an audience, what are we doing any of this for?

Comments : 1 Comment »

Tags: alienation, Andres Serrano, art, Broken Mic, Clement Greenberg, contemporary culture, Culture Wars, LeBron James, Modernism, NEA, open mic, Piss Christ, postmodernism, public arts funding, Spokane Arts Commission, The Undertaker

Categories : Art, Art Outside the Gallery, Poetry

Legend, Myth, and Street Cred in the Image of the Artist

2 06 2012In the world of slam poetry, having a difficult life about which to write can be a distinct advantage. Let me be clear. I am not saying that coming from poverty, racial discrimination, domestic violence or homophobia are advantages in life. I am saying that plumbing the depths of those experiences in writing and performing slam poetry can bring high scores from judges, adoration from audiences, and respect from other poets in ways that writing about a middle-class white suburban upbringing to do not.

Much of this is due to the personal nature of slam. Poems are often windows into the lives of the poets themselves. They aren’t writing about an abstract idea of racial prejudice—they are writing about their own experience with it. As an audience, we feel like we know the person through his or her poetry.

This is not something that is limited to slam. We look for clues into the life and psyche of an artist through his paintings, of a novelist through her words, or of a rapper through his songs. The more hardship that we find, it seems, the more connection we feel to the artist through the work. In slam, this is immediately apparent through scores, but it happens in all forms of cultural production.

Every person on this planet experiences hardship of some sort—even rich people, even white people. When an artwork addresses hardship in a way that magnifies suffering, it ennobles suffering. The audience can then apply that nobility to their own suffering while at the same time connecting with the suffering expressed by the artist (even if they have nothing to do with each other). Empathy and catharsis are achieved in this communication.

An example of how this works with a fictional character can be found in the TV show House. Gregory House, the genius diagnostician, suffers from chronic pain due to an infarction in his leg suffered years ago. The pain is so great, it affects how he relates to his employees, his patients, his love interests, and even his best friend, Wilson. He develops an addiction to Vicodin as a result of coping with this pain. Everyone in the audience has experienced pain. Chances are it is neither the level nor duration experienced by House, but pain is pain—physical, emotional, or psychological. Everyone in the audience has had to cope with pain. Maybe it hasn’t been through Vicodin—maybe it’s alcohol, maybe it’s exercise, maybe it’s watching television or writing blogs about art and contemporary culture. However small the scale of pain may be for a particular audience member, the magnitude of House’s pain gives credence to how big the pain FEELS to the member of the audience. He relates to House because House is like him, even though House is nothing like him.

Yet, House is a fictional character. Our expectations of the lives of artists is more stringent. We expect artists to relate to us out of real pain, not fictional pain. We look for signs of insanity in the paintings of Vincent Van Gogh or the poems of Sylvia Plath, because we know the paths their lives really took. We also expect poets, musicians and rappers to have actually lived the lives they write, sing, or rap about. As a result, artists of all stripes are either respected for fitting the expected mold of lifelong hardship or strive to make their lives fit that mold.

In art, the most obvious case of fitting the mold is Jean-Michel Basquiat. He was the ultimate un-trained street artist-cum-multi-millionaire gallery superstar who got his start sleeping on park benches and tagging graffiti all over New York. He also came from an upper middle-class family, studied at the Edward R. Murrow School, and could speak fluent Spanish and French (as well as English) by age 11. His identity as an outsider or underdog was constructed and marketed—partially by him, partially by Annina Nosei and Mary Boone. His work is generally accepted (though not necessarily hailed) by critics and he is adored by art students because of his (manufactured) outsider status—something that is a prerequisite of the hero artist.

Insider artists, even if they sell, are generally reviled as charlatans, as disingenuous. It seems as if Jeff Koons has “former bond trader” permanently attached to his name in print, as if to consistently remind us that he is not from the bottom of society—his is not a life of hardship and struggle. This is precisely what happened to Vanilla Ice.

Unauthorized sampling of Queen’s “Under Pressure” aside, “Ice Ice Baby” is a much harder song than it gets credit for. Record companies did not know how to market rap just yet, so Vanilla Ice’s look and video from 1990 are seen as laughably innocent compared to the gangsta rap that was about to come straight outta Compton. But the lyrics are not that far away from those of NWA:

Yo, so I continued to A-1-A Beachfront Avenue

Girls were hot wearing less than bikinis

Rock man lovers driving Lamborghini

Jealous ’cause I’m out getting mine

Shay with a gauge and Vanilla with a nine

Ready for the chumps on the wall

The chumps are acting ill because they’re so full of eight balls

Gunshots ranged out like a bell

I grabbed my nine

All I heard were shells

Fallin’ on the concrete real fast

Jumped in my car, slammed on the gas

Bumper to bumper the avenue’s packed

I’m tryin’ to get away before the jackers jack

Police on the scene

You know what I mean

They passed me up, confronted all the dope fiends

If there was a problem

Yo, I’ll solve it

Check out the hook while my DJ revolves it

No swearing, no sex (really), but plenty of gang, violence, and drug references. But Vanilla Ice was never taken seriously, and certainly not as seriously as Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, Tupac Shakur or Notorious B.I.G. Aside from the Parliament/Funkadelic sample and the “Parental Advisory”-inducing swearing, Snoop’s debut single, “What’s My Name,” is remarkably similar in content to “Ice Ice Baby”—a lot of boasting and name repetition.

Vanilla Ice’s record company tried to increase his street credibility by publishing a false biography in his name which, among other things, connected him to 2 Live Crew’s Luther Campbell. His own life story didn’t need embellishing—he had just as difficult a childhood as any other rapper who grew up in a broken home, never knowing his real father. Nonetheless, with no credibility due to the fake biography added to the glitzy packaging and the fact that he is white, Vanilla Ice (whose given name is Robert Matthew Van Winkle) became a joke as quickly as he had become a star.

Audiences expect rappers to live the thug life about which they rap—50 Cent earned fame as much for having been shot as for his skills as a performer. Audiences also expect slam poets to have lived the experiences they are communicating in their performances. Combined with the expectation of empathy through stories of hardship, this means that poets of color, queer poets, and, at times, women poets can make stronger connections than straight, white, male poets. The connection is reflected in scores and audience response.

Curiously, in an effort to make this all-important personal connection, many slam poets in recent years (minority poets included) have turned to the persona poem. A persona poem is when a poet writes about a person who is not themselves from a first-person point of view. The team from St. Paul, Minnesota won the National Poetry Slam two years in a row, largely with the help of persona poems by 6 is 9 (Khary Jackson) and Sierra DeMulder. The persona poem has opened an avenue for poets to connect to audiences with stories of hardship that may be outside of their own lived experience. But even this can backfire.

In 2007 in Austin, Alvin Lau took second in the Individual finals at the National Poetry Slam. One of his higher-scoring and more well-received poems dealt with a lesbian sister. As it turns out, Alvin Lau does not have a lesbian sister. It’s impossible for me to know how audiences have reacted to that revelation, but poets have been largely unforgiving of Lau for using hardship outside of his own experience in order to increase his standings in this competitive art from. It was two years later that St. Paul won its first of two consecutive NPS titles with persona poems.

Earlier this week, poet Rachel McKibbens posted a link on her Facebook page to a blog with the headline “Do We Need Affirmative Action for White Male Poets?” McKibbens has long been outspoken about the gender disparity in slam audiences and in slam champions (which is predominantly male), and she posted the link out of indignation. To me, the blog comes across as a father who thought his son did better than the judges scored (surely an expected response from a proud parent), and had very little experience with the form of slam poetry itself

I was struck by the outrage of the comments about the post. Many reacted just to the headline, addressing nothing within the article. Chicago poet Billy Tuggle went on record refusing to read it, saying “Fuck this dude.” Sierra DeMulder was quoted, derisively saying, “What a tragedy, young, white, poet man.” DeMulder’s best-known poem, “Mrs. Dahmer,” is a persona piece from the perspective of the mother of a mass murderer

As a white male, it can be difficult to connect with audiences expecting empathy and catharsis. My race and class provide me with opportunities that make my life easier than lives of others. We do not live in a classless or post-racial world, no matter how much anyone tries to sugar-coat it. Despite differences, pain is a condition of human existence. No matter our race, no matter our background, we can relate to each other as people through this universal conduit. It may be that to better connect with an audience as a poet, you have to become a better writer and performer. To better connect with a viewer as a painter, you have to become a better artist. To become better artists, we have to become better communicators.

Comments : 3 Comments »

Tags: 6 is 9, Alvin Lau, art, contemporary culture, Ice Ice Baby, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Jeff Koons, Khary Jackson, Mrs. Dahmer, Rachel McKibbens, rap, Sierra DeMulder, slam poetry, Snoop Doggy Dogg, Van Gogh, Vanilla Ice, What's My Name?

Categories : Art Outside the Gallery, Poetry

Thomas Kinkade is Dead. Long Live Thomas Kinkade.

15 04 2012When Thomas Kinkade died last week, I got a few emails and Facebook wall posts from former students. “I don’t know why, but I feel compelled to inform you about this.” I have had a long and complex relationship with the art of Thomas Kinkade, and his death brought him to the forefront of the greater consciousness (however briefly) once again.

This is an example of a Thomas Kinkade painting. There's no need to look at any other ones, they're all pretty much this.

Thomas Kinkade was a painter. He was a very well-known painter who produced thousands of paintings of quaint cottages in idyllic settings. Tomas Kinkade was a businessman. His galleries are in malls all across America. There are calendars, coffee mugs, prints of various qualities and price ranges, “original” paintings, and even a Kinkade-themed housing development in Northern California. For most in the art world, this places Kinkade firmly in the category of kitsch, with his reliance on mass reproductions of artworks and an easy appeal to a general populace.

When I was a graduate teaching assistant, instructing introductory-level studio classes, our first-day activity was to have the students fill out a form answering various questions about themselves. What kind of music did they like? What other art classes had they taken? And, of course, who was their favorite artists. When the TAs would get together after the first day, the conversation always turned to that last question. How many Van Goghs did you get? How many Dalís? Any late, great, unknown uncles? And the kicker—the question that would make us howl with laughter and wretch with disgust—how many Kinkades? We were snobs. We were art snobs. We were educated art snobs, and we were going to educate these uninitiated undergrads about what was good and what was bad art, and Thomas Kinkade was bad art.

There are several factors that go into dismissing Kinkade outright, and the kitsch argument is only one of them. His galleries, even if they were not franchised McDonald’s of paintings scattered across America and found next to the Dillard’s north wing of the mall, were vanity galleries. A vanity gallery is an art gallery that is owned and operated by the artist himself or herself. While academic art instruction sees itself as operating outside of the art market, the market’s peculiar institutions of legitimation are sacrosanct.

A gallery, in the operation of the art market, is a proprietorship of a connoisseur who gathers the work of a group of artists, legitimized by their inclusion in this stable (yes, this is how the collection of artists represented by a gallery are referred to). The connoisseur in the form of the art dealer then sells the work to connoisseurs in the form of the buyers. The connections and collecting history of the connoisseurs provide the provenance for the work, and the connection with that provenance further legitimizes the artist. They aren’t just making great work. It’s great because of who owns it and because of what else they own or have owned. A Jenny Saville isn’t just important because it’s a monumental painting, but because it was purchased by Charles Saatchi, and Saatchi also purchased work by Damien Hirst and Sam Taylor-Wood. Good connections in the primary market lead to even better connections in the secondary (auction) market, which lead to collection or donation to museums, which are the ultimate arbiters of what is important. What is important to museums is what ends up in art history text books, and it is what is taught to students as high art. This process, as convoluted as it is, begins in the person of the art dealer.

In a vanity gallery, the artist circumvents the dealer in order to get his or her work to the primary market. The work is sold, yes, but in the view of the institutions of legitimation, a necessary step in gaining legitimacy has been skipped. How can these primary consumers know what they like if they don’t have a connoisseur to tell them what is important? Thomas Kinkade made the vanity gallery into Wal-Mart, selling directly to consumers, legitimation be damned.

Aside from the inconsequential, saccharine-sweet subject matter of Kincade’s paintings, his primary sin in the eyes of the art world is this crucial skipped step. Other popular kitsch artists are simply ignored: Maxfield Parrish, Norman Rockwell, Anne Geddes, whoever took those photographs of children in adult clothes in the 1980s. For those who hate Kincade, he is more than ignored, he is reviled, and other “sins” are held up as support for this judgment that are allowed to pass with other artists—even artists widely recognized by the institutions as important.

Even as a student myself, I lambasted Kinkade’s use of employees in creating his works. “They aren’t even his!” I would argue, “He’s just the financier! He’s a businessman. Not an artist.” Many people share the expectation that the genius artist’s hands are the only hands that work toward creating the final object. The image of the artist’s studio in the heads of art students and the general public alike is one of a lone artist, toiling away at his massive projects.

Art is not made this way. For an artist to make money, very rarely is this even a possibility. In pre-Modern art eras, the sole-genius-production ideal was not as closely held. Renaissance artists like da Vinci and Michelangelo were part of a guild system, where apprentices would do basic work like backgrounds in paintings or rough out the major forms for a sculpture. The master was the boss in this situation, but the workload was shared. Four hundred years later, Monet used apprentices and employees to crank out painting after painting of water lilies and haystacks. In the 1960s, Andy Warhol went so far as to refer to his studio as The Factory, with artists, actors, photographers, and even lackeys all contributing to its output. Jeff Koons and Takashi Murakami do not lay a finger on the massive sculptures and paintings produced and exhibited under their names. These artists occupy the highest tiers of the art-historical hierarchy (Koons is certainly up for debate—another blog on him later), and their output is directly related to the use of employee artisans to physically create the works.

I have written at length about the dangers of high art alienating itself from the tastes and opinions of culture at large. The disdain for items produced for a consumer, mass, or popular market is self-defeating. How much differently would high art be perceived if Alan Kaprow’s Art Store had been in malls all across America? What if connoisseurship was permanently circumvented and every person’s opinion had equal validity in the market? What if legitimation depended more on quality of communication than quality of provenance and connections? Would Kinkade have died an art start? Would his paintings be in the Powerpoints of 100-level Art History survey courses?

In many ways, Thomas Kinkade fit the mold of the superstar hero artist. He had ambition, ego, and is even rumored to have died due to alcoholism. In the pantheon of art gods, those qualities have eclipsed any technical talent since 1956. Personally, I can’t stand the work of Thomas Kinkade. I also hate the Rococo. But the Rococo has a place in art history textbooks. Maybe Thomas Kinkade should, too.

Comments : 3 Comments »

Tags: Allan Kaprow, Andy Warhol, art, Claude Monet, Clement Greenberg, Damien Hirst, Jackson Pollock, Jeff Koons, Jenny Saville, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Sam Taylor-Wood, Takashi Murakami, Thomas Kincaide

Categories : Art, Culture, University Art Education

Daniel Tosh is Important

1 04 2012Daniel Tosh is a stand-up comedian and television host. I doubt many people would describe him as particularly socially-conscious in either of those roles. His show, Tosh.0, is a hybrid of stand-up, sketch comedy, and internet video commentary and includes potentially offensive material in bits such as “Is It Racist?” and “Rico’s Black Clip of the Week.” I think that Daniel Tosh, and Tosh.0 in particular, is a prime example of postmodern entertainment that pushes the boundaries of social issues in a way that results in elevated discourse rather than crass exploitation.

Tosh.0 is Postmodern

The television show is nowhere near original. Despite my description above, it is inherently a clip show. Its reliance on home videos posted on the internet make it the America’s Funniest Home Videos of the 21st Century. The format of a host in front of a green screen commenting on clips owes its existence to Talk Soup (later re-named The Soup), originally hosted by Greg Kinnear.

Of course, something doesn’t have to be original to be entertaining. Tosh’s style in delivery and class clown grin make the show engaging and somehow personal, and the adult content of both the videos and the commentary give the show a bite not found in either television predecessor. The show plays like a highlight reel of internet comment posts, weeding out the merely shocking, racist, or pithy and showcasing the truly snarky and hilariously cynical.

The unoriginality of the show seems to categorize it as mere pastiche, but Tosh.0 is unabashedly self-aware. From the inclusion of the writing and production crew in sketches to the mockingly prophetic sign-offs before the final commercial break of each episode (Tosh signs off with a reference to a cancelled Comedy Central show: “We’ll be right back with more Sarah Silverman Program!”), Tosh highlights not only the mechanisms of the show’s production, but also the reality that the lifespan of the show itself is limited. The sign-off was perhaps more prescient in the early days of the show. As with many Comedy Central shows, its low production costs come with low expectations from the network—cancellation of a Comedy Central show is a foregone conclusion. That is, of course, until it catches fire like South Park did, or Chappelle’s Show, or even The Daily Show.

Tosh has also made reference to his predecessors on air. “Hey, I heard there’s some show called The Soup that totally ripped off our format! The idea for this show came to me in a dream! With Greg Kinnear, except it really wasn’t Greg Kinnear…” In this season’s Web Redemption of a horrible sketch comedy trio, Tosh led the segment saying, “Hey, sketch comedy is hard. If someone brilliant like Dave Chappelle can go crazy doing it, what makes you think you’ll be any good?”

Tosh.0 is Socially Conscious

The fraternity with Chappelle is based on more than that of hosting popular Comedy Central programs. Richard Pryor paved the way for Dave Chappelle, and Dave Chappelle paved the way for Daniel Tosh.

Chappelle is credited for approaching issues of race in a comedic way on television unflinchingly and uncompromisingly. He made fun of racism—not just white racism toward blacks, but also black racism toward whites and Asians, and even other blacks. It can be cynically concluded that Chappelle and Pryor (who did the same thing thirty years earlier in stand-up comedy) could get away with calling out black racism because they themselves were (are) black. Daniel Tosh proves that the race of the commentator is not the determining factor for this kind of statement.

The clip that spawned the recurring bit, “Is It Racist” was a video of an Asian toddler in a pool, held afloat by his or her head suspended in a plastic floating ring. Among many jokes, Tosh cracked, “Is it racist if I can’t tell if her eyes are open or not?” After a brief pause, he said indignantly, “I’m saying ‘Is it?’ Yes… yes, I’m being told by the audience that yes, it is racist.”

Jokes about racism regarding African Americans, Latinos, Asians, Jewish people, and even white people are all approached with a level of honesty and self-effacement that makes them engaging rather than mean. In a web redemption from this season, Tosh interviews a couple who’s wedding was ruined by a sandstorm. The groom was Mexican and the bride was white. Rather than shy away from racial comments when in the actual presence of a minority, Tosh addresses it head-on. Any menace in this line of questioning is deadened by the fact that Tosh is conducting the interview in a heart-shaped hot tub. He often uses the physical appearance of his own nearly-nude body to neutralize potentially heated or offensive confrontations. It also helps that during these interviews, he is unabashedly positive, which is unexpected given the bite of the rest of the show.

Context is key for Tosh’s approach to topics like race, sexuality, abortion, and religion. He is making jokes, yes. But his delivery and his appearance, as well as the jokes themselves, communicate an awareness of his own place in the larger issue underlying the comedic bit. In comparison, it is much harder to see positivity in the comments by viewers on Tosh.0 blog posts. Many comments come across as simply racist, rather than as addressing racism.

Below is the clip of the Asian “Neck Tube Baby” bit from Tosh.0. Not only is it an example of Tosh’s approach to race, it also includes the show’s characteristic reflexivity, acknowledging the production of the bit itself.

Daniel Tosh is Uplifting

I’ll be honest. For the first two seasons of Tosh.0, I changed the channel or left the room during the “Web Redemption” segment. I’ve never been a fan of cringe-inducing comedy, and the idea of taking someone’s most embarrassing moment, already broadcast to the entire internet, and making a seven-minute television segment based entirely on that moment, seemed too mean-spirited and too awkward for me to watch comfortably. My fears were unfounded.

Tosh brings the people in question to Los Angeles and interviews them to begin the segment. The interview includes the cracking of jokes, of course, but Tosh is truly laughing with the interviewee. The redemption part of the segment is typically cheesy. The person gets a second chance to complete whatever task when awry and got them internet famous for some sort of mistake. A girl gets a chance to walk down stairs in a prom dress without tripping. A guy gets a chance to park a Ford Mustang in a garage without running it through the wall. Typically, in these bits, Tosh is the main point of comedy—often employed through the use of a goofy costume such as the Pope outfit worn for the redemption of the married couple mentioned earlier. Most of the time, the person succeeds in their attempt to redeem themselves, even though that redemption is a little low in the area of a pay-off. They still have the internet embarrassment out there, though by now they’ve probably come to terms with it. Heck, they did agree to be on a show knowing full well that the embarrassing moment was the reason for their appearance.

In some cases, however, the person fails in their comedic-sketch attempt at redemption. Tosh uses this to aim the humor away from the person involved, however. An appearance by Ron Jeremy after a girl falls down the stairs in a prom dress for a second time becomes a joke about Ron Jeremy (Ron Jeremy is his own joke about himself). Dennis Rodman appears from nowhere to block a man’s attempted trick basketball shot. That was perhaps my favorite save. On returning to the set (these bits are shot on location and shown as clips during the hosted show), Tosh points out that for $5,000, you can have Dennis Rodman show up at your house and do whatever you want… for about five minutes, which mocks the show for paying that much for the cameo and Rodman for shilling himself out so shamelessly.

Daniel Tosh is Important

Daniel Tosh is not what I would consider an activist comedian. He’s not out to make some great social change in the world. He’s out to make people laugh and, if you believe his shtick, make a lot of money doing it. But performers don’t necessarily have to be performing ABOUT an issue to make a difference regarding an issue. It’s often a matter of bringing the conversation up. If that approach is comedic, the conversation is that much easier to start. Tosh’s approach is more high-brow than it may seem at first glance, and for that, we thank you.

Comments : 1 Comment »

Tags: America's Funniest Home Videos, Chappelle's Show, contemporary culture, Daniel Tosh, Dave Chappelle, Dennis Rodman, Greg Kinnear, Pastiche, postmodernism, reflexivity, Richard Pryor, Ron Jeremy, South Park, Talk Soup, The Daily Show, The Soup, Tosh.0

Categories : Culture, Our Postmodern Reality

Inside/Outside

18 03 2012Howard Singerman opens the sixth chapter of Art Subjects: Making Artists in the American University by pointing out not only the primacy of language in university art education, but also the place of the artist in the work and in the instruction of art itself. In an age of conceptual art, with language being a large factor in both the construction and understanding of a work, the artist’s statement and the artist’s talk are not just addendums to the work—they are the work.

Universities and museums become a sort of circuit for conceptual and alternative media artists, like night clubs for a band or book-signings for an author. Since large municipal museums are unlikely to show the work of lesser-known artists, and galleries have a hard time promoting their work due to a lack of physical commodities to sell in many cases, the most ephemeral, most conceptual kinds of artwork are promoted through the institution of the university. In these cases, artists come with the work—it’s not just a bunch of paintings in a crate. They help with the installation (in some cases the work is actually produced at the university), visit studios of upper classmen and graduate students, and typically give a presentation on their work.

This kind of interaction with the artists has a powerful effect on students. When they are so intimately involved with the artist and with the creation of the work (when that occurs), the possibilities of conceptual and non-object-based work can seem very exciting. They are, indeed. It is those possibilities upon which this blog is based.

The problem with this model for art legitimation is that it ends up being a circular system. Conceptual artists have too small of a market on which to sell their works, thus getting them into the primary market of collectors, the secondary market of the auction houses, and finally the legitimization that comes with the acquisition of their work by a noted museum and the textbook recognition that comes with that. They, in effect, cut around the market part of that system and are injected directly into the legitimization of the curriculum by becoming an active part of it.

The market for conceptual work is not the art (commodity) market. It is the university. So students inspired to work this way then go into the market that exists for it: the university from whence they came. They want to become an artist like Chris Burden (see page 161 of Art Subjects for an amusing example of one of Burden’s artist’s visits), getting stipends for artist’s talks. They want to become university art instructors—to be able to make a living involved with art while producing the kinds of work they themselves are legitimating. Quoting Raymond Parker, Singerman states, “The taught art world determines the status of the teachers in the eyes of the students: ‘The teacher distinguishes himself from the student by the authority with which he acts as a part of the art world (p. 158).’” While Burden was teaching at UCLA, a student (not in one of his classes), payed homage to this iconic performance by seeming to run out of the classroom and commit suicide as a performance. Burden resigned as a result, not wanting to inspire further and perhaps more reckless actions by students. The incident highlights the kind of influence instructors have over students in what they produce and in what they promote.

The problems with this system are twofold, but they both center on the insularity of the system. First, the legitimation of artists taking place within the university alienates those outside of the university, more specifically—those outside the university art department. While the intimate interaction with the artists is indeed powerful for the students, faculty, and the relatively small number of community attendees involved, it is not a part of the experience of those who just come into the gallery to see the exhibition. A video projected on the wall of crowds of people bustling about their day might have been an intense and rewarding work of collaboration for a visiting artist and a group of students, but it has no power for the pre-med major wandering through between classes who wasn’t present for the artist’s talk the day before. To her, it may just be another weird video installation in the art department—they’re always doing strange things over there. As I’ve stated elsewhere in this blog, when art is treated as a curiosity rather than as essential, its place power in the larger society is greatly diminished.

Secondly, this system produces graduates who are trained to make artwork for this insular system. Students get BFAs in order to get MFAs. They get MFAs in order to teach. They teach students working toward BFAs, and the circle continues. This system may not be a problem, if not for the small size of the pool of instructors. At the university where I taught for five years, there were over 900 declared art majors Fall Semester of 2012. There were 24 full-time art faculty.

The odds of becoming a big, rich, rock star are recognized as small—there can only be one Metallica out of the millions of metal bands playing shows in dive bars in small towns. The odds of becoming an art star are similarly small (maybe even smaller) and even art students, as optimistic as they may be, understand that. Of the tens of thousands of MFA graduates in the United States every year, there are under 1000 graduate programs, and each may be hiring one to three full-time faculty in a given year, if any. The turnover rate for tenure-track professors is not high.

As an undergraduate, I was inspired to work in conceptual and performance art by the work of my Alternative Media professor at Eastern Washington University, Tom Askman. Visiting artist Rirkrit Tiravanija got me excited about exploring the experiential and the idea that anything—even cooking for strangers—could be art. A studio visit from Juane Quick-To-See Smith encouraged me me to go to graduate school. An extended graduate studio visit from Joanna Frueh and the knowledge that the artists I most admired—Allan Kaprow, Guillermo Gomez-Peña, and Enrique Chagoya—had experience teaching while producing art stoked my optimism when I graduated. It seemed very possible that I would one day be able to have a stable income while making art and even potentially making a difference in art.

For all the talk of conceptual, interactive, alternative media-based art and its potential to reach outside of the institutions of art and engage the larger population, both the inspiration and the occupational stability for those artists comes from within the institution. Here, the university has replaced the gallery and the museum. An art artist creates work within the educational setting, which inspires students to work in similar ways in order and end up legitimized by that educational setting. For all my rhetoric about operating outside of academia (yes, I talked about it even as a student), my plan was to seek employment within.

For five years, I taught as an adjunct instructor at the university where I earned my MFA. In those five years, I applied for so many tenure-track positions, I lost count. In those five years, I was never so much as interviewed for a position. I do not know the reasons for my unemployability in the academic field, and to guess at what they may be would be misguided. The point is that I have finally moved to a different field. Last week, I got a “real” job. Outside of the university, outside of the art world—this job is far from thinking about how everything and everyday can be an art experience.

My training and expertise in Derridean Deconstruction and Semiotics mean little in my current position, and by “little” I mean “nothing.” After twelve years as either an art student or an instructor, it’s strange to go to work every day in that “real world” I always talked so passionately about. My challenge is to continue to incorporate the ideas of Kaprow, Singerman, James Elkins, Yoko Ono, Joseph Beuys, Marcel Duchamp, Arthur C. Danto, Lucy Lippard, Suzanne Lacey, Rachel McKibbens, Cheryl Maddalena, Nick Newman, and the other artists, writers, theorists and poets who influenced me into my own experience of everyday life.

The cliché goes, “If you do what you love, you never work a day in your life.” For five years, that was my life. Now, I have to work. Make no mistake: this is not a self-pitying blog post. I am not resigning from performing poetry, writing blogs, organizing events, or critiquing every form of cultural production that crosses into my field of vision. I will continue to make art. I now have the challenge of making art truly outside of academia—in the “real” world.

Works Cited:

Singerman, Howard. Art Subjects: Making Artists in the American University. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999.

Comments : 3 Comments »

Tags: Allan Kaprow, art, Arthur C. Danto, BFA, Boise State University, Cheryl Maddalena, contemporary culture, Eastern Washington University, Guillermo Gomez-Pena, Howard Singerman, James Elkins, Joanna Frueh, Joseph Beuys, Juane Quick-To-See Smith, Lucy Lippard, Marcel Duchamp, meaning, MFA, Nick Newman, Rachel McKibbens, Rirkrit Tiravanija, slam poetry, Suzanne Lacey, Tom Askman, Yoko Ono

Categories : Art, Art Outside the Gallery, University Art Education