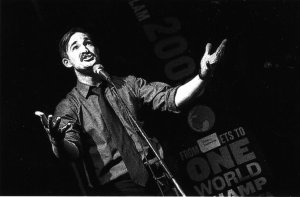

I am a regular patron of Broken Mic, a performance poetry open mic in Spokane, Washington. The average age of both audience and performers is somewhere in the late teens and early twenties. There’s a lot of angst, altruism, and shock value and even more support from poets and the audience. That support is not, however, unconditional. In April, a poet stood in front of the audience for the first time ever, and prefaced his poem by saying, “I wrote this poem about butt sex and I’m going to do it even if there are little kids here, so fuck you.” By the time he was finished, he was hearing boos as he went back to his seat.

The content of the poem didn’t bother me. Shock and vulgarity are used in many instances to gain attention. While I think his poem lacked in the category of substance, writing about something that is culturally taboo and performing it in an atmosphere that promotes free speech shouldn’t be a problem. The fact that there was a six or seven year old child in the front row doesn’t bother me, either. The mother was present, there is an announcement at the beginning of every event making it clear that poets can and will say things that offend. If she had wanted her son to not be present for this display, she could have left well before the offending poet made it to the microphone.

Where the poet erred was in alienating the audience. Leading off by telling the audience to go fuck itself put the performer at odds with them before they even knew who he was or what he was all about. American audiences hold self-assured artists in high regard, but not before they’ve either paid their penitence or demonstrated their work as being of the highest quality. We may delight in the character of the villain, but we always expect the good guy to win in the end.

LeBron James alienated a nation of basketball fans in 2010 by leaving the Cleveland Cavaliers for the Miami Heat. He compounded the alienation by announcing his decision in an hour-long televised special, the team holding a celebratory pep rally before the newly-formed group had even held one practice, and James telling the crowd that they would win “not two, not three, not four…” but eight championships. Cleveland fans burned his jersey in the streets. The rest of the basketball world decried this hubris, and LeBron, for the first time in his life, found himself cast as the villain.

James and the rest of the team embraced this role as they pursued a championship in the 2010-2011 season. While American audiences take a certain pleasure in villainous characters like Frank Costello in The Departed or The Undertaker in professional wrestling, they have little sympathy for a villain who has not accomplished anything. LeBron, who had come straight into the NBA out of a ridiculously-hyped high school career, had never received any kind of disapproval, certainly nothing on this scale with this kind of vehemence. The villain role was not something James and the Heat could fill, and their loss to Dallas in the 2011 NBA Finals was the equivalent to getting booed off the stage after an indignant poem about anal sex.

LeBron alienated the public by very visibly and very publicly demonstrating that he did not care what they thought. Of course, he did care, and was genuinely hurt when the public reprimanded him for his actions. Whether he wanted to admit it or not, the poet from Broken Mic in April was hurt by the boos as well. At the heart of the actions of both was a fear of rejection, which was all but guaranteed.

If a kid wants to protect himself form schoolyard mockery, one tactic is to display that he does not care what the mocking children think. If they get no response, the mocking is fruitless and they move on. If a performer is putting herself in front of an audience with the danger of not being approved, she can mitigate the rejection by claiming to not want the approval in the first place. Superficially at least, both sides come away as if they’ve won. The audience has rejected the performer for hubris, and the performer has rejected the audience’s lack of approval by saying she was never seeking it. “Of course they didn’t get it. They’re just too simple to understand…”

We can compare this attitude to the Greenbergian notion of the separation of high Art from the rest of life. For Greenberg, if Art was to progress and advance, it needed to be separate from the rest of society—artists should not worry about the approval of the masses. Non-educated art patrons and popular audiences were to be ignored in favor of focused investigation into the specific area that was High Art. A painting did not exist for the enjoyment of some schmo on the street—it existed for the sole purpose of being a painting.

The authority embodied in the artist (here, Jackson Pollock) and the critic (in this case, Greenberg) made the hubris of High Modernism titanic. In a postmodern age of skepticism, authority isn’t what it once was.

On the one hand, this alienates the larger public. On the other hand, it provides a group for artists to identify with. There is a cachet that comes with being an insider—whether it’s in a dance-club scene, the world of high art, or poets in Spokane. The attitude paradoxically justifies whoever holds it as both an individual (in rejecting the expectations of “the masses”) and a part of a group of artists, writers, performers, or thinkers who hold similar attitudes, education, and experiences. The attitude of specialization inherently creates cliques, and if we remember anything from Junior High School, cliques get jealous of other cliques.

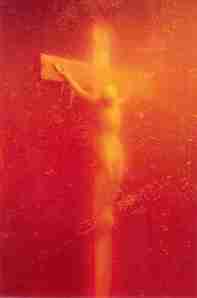

In 1989, Piss Christ, a photo by Andres Serrano, became the flashpoint in what would come to be known as the Culture Wars. Without simplifying the issue too much, the photo was given an award that was funded partly with money from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). This enraged conservatives who used the image and the award as reasoning to cut funding to the NEA.

The fact that it was a photo escaped some politicians. The fact that it was among a series of other photos of different objects and figurines submerged in a mixture of urine and cow’s blood escaped almost everybody. The formal or conceptual considerations of Serrano were moot points in the larger discussion—the shock was all that mattered. It was an inflammatory image with an inflammatory title. This, combined with the already entrenched attitude of the art elite dismissing the approval of wider audiences, meant little sympathy and little resistance to the evisceration of the NEA’s funding of the visual arts.

In 2012, the political climate again has public funding for the visual arts on the ropes. In Spokane, there is much hand-wringing over the fate of the Spokane Arts Commission, which has already seen a long series of cuts which has left it a shell of a “commission” with only one employee and a handful of volunteers. The Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture (known as the MAC) has fired its director for undisclosed reasons and is facing the ire of the public for this decision and a demand for an explanation. The MAC has also been forced to look for private sources of funding as public money for visual art in the region has dried up.

Outside of the people actively involved in the arts in Spokane (which consists in no small part of artists themselves), there has been little protest over the possibility of doing away with the Spokane Arts Commission. The Commission oversees the acquisition and maintenance of public art projects in the city from the Harold Balazs sculptures floating in the river to the garbage-eating goat to the murals on railway underpasses. It is an organizational hub for small non-profits from Saranac Art Projects to Et. Al. Poets, and, yes, it helps those organizations find, apply for, and get government grants.

The Spokane Arts Commission is on the precipice of nonexistence not because of anything it does, but because of an attitude perpetuated by those involved in High Art. We ignore mass audiences at our own peril. By continuing to isolate ourselves and dismiss the larger public, we make what we do appear to be something other than necessary. What’s worse, the expectation of government funding has led to ignoring potential customers. If we do not expect them to pay to see what we have to offer in person, how can we expect them to think it is necessary to pay via taxes if they don’t (or aren’t even invited to) see it?

The problem isn’t with the product: poetry, art, music, and plays are as vibrant in Spokane now as they have ever been. The problem is in perception—it’s in marketing; it’s in public relations. If we abandon the idea that art should be separate from the rest of life, those people who decide how art is funded and therefore how artists can live will see it as a necessary part of life. This change in attitude starts with the artists and performers. It starts with conversations. It starts with including anyone who is even remotely interested and alienating no one—even if what you are saying with your work is confrontational.

With inclusivity, art can be a valued part of everyday life, and everyday life can be a valued part of art. We aren’t going to force anyone to pay attention to our work by telling them we don’t care what they think. We have to care. Without an audience, what are we doing any of this for?

Mark Zuckerberg and Troy Davis

23 09 2011Karl Marx famously stated that “religion is the opiate of the masses.” By this, he meant that the institution of religion keeps the masses satiated and compliant to the will of those in power—those with the capital, those whose ultimate goal was profit above all else. Clement Greenberg had similar ideas about kitsch (though he would be appalled to be so closely linked to Marx). Kitsch satisfies the uncultured, the uneducated, and can be used by those in power to manipulate the opinions and will of the people to their own ends. Walter Benjamin saw similar potential in entertainment, specifically in film—both Benjamin and Greenberg saw the way Hitler used propaganda and mass-appeal to his own ends as examples of entertainment, rather than religion, as the opiate of the 20th Century masses.

“Entertainment” as such is a bit more difficult to pin down in the age of simulacra, pastiche, and the hyperreal. It has become ubiquitous and constant in American culture—the rise of the smart phone has brought the power of the internet into the palm of your hand. Yet this power is used more often to play Scrabble with friends or fiddle around on Facebook or Twitter. One never has to wait to be entertained by an inane post from a friend, a Star Wars/kitten meme, or an insipid 140-character rant from a B-list celebrity or athlete. Even while waiting in line at the movie theater to be entertained, we seek entertainment from our phones.

The infinite power of the internet... at its best.

The power of Facebook is both greater and less than it is purported to be, either by media outlets or by its own self-promotion. There was fanfare and congratulations over the role the social media site played in the Arab Spring, with much media attention centered on its use in Egypt. “Facebook made democracy possible in an oppressed country,” seems to be the underlying attitude of many. But Facebook did not liberate Egypt: Egyptians did. Surely, there was some communication between protesters that did take place on the site, but it was the protests and actions taken by the people, and their resistance against being put down by force, that ultimately resulted in regime change.

Still, the perception of Facebook as the ambassador of democracy to a troubled region has led to an inflated sense of both pride and confidence among Americans. Since the ideology of democracy is at the core of our identity (i.e. “Democracy is Good”), and Facebook helped bring democracy to the Middle East, then Facebook is an example of democracy at its finest. This, of course, is not true.

Facebook was invented, and is only possible, in a country that holds the Freedom of Speech in high regard. Facebook is not a democracy, it is a corporation—a private enterprise. The content placed on Facebook is the sole property of Facebook itself, which can censor anything it chooses (so far, it has chosen not to censor and has been banned in China since 2009 as a result). It can also make changes however it pleases, regardless of what its users may think about the changes. This week has seen a major change to the layout of the site, with some new features added, and has brought the “wrath” of its customers, with countless angry posts (on Facebook) complaining and demanding a change back. Mark Zuckerberg is not going to change it back.

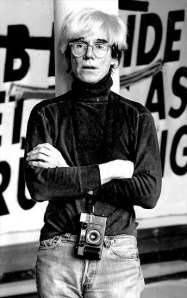

This twerp's a billionaire. Do you honestly believe he gives a crap about what you think?

This is not the first time Facebook has made changes, and not the first time its users have been upset. In the end, by and large, the users don’t leave. There was an outcry over rules changes in 2009 that ultimately did pressure a reversal of stance by the website. However, as far back as 2006, the “Students Against Facebook News Feed” group pressured the site to give some control to users to “opt out” of the news feed feature. In 2009, those controls were removed. In 2010, nobody was complaining about their lack of control of the news feed. A year ago, the site made a gradual change to a “New Profile,” that initially seemed voluntary, until the “New Profile” was the only option.

What is dangerous is that Facebook provides the illusion of democracy outside of itself. Jean Baudrillard made similar statements about the hyperreality of Disneyland. Baudrillard is not concerned with the fiction that Disneyland presents (i.e. a cleaned-up version of American Main Street), but its function as a “deterrence machine… It’s meant to be an infantile world, in order to make us believe that the adults are elsewhere, in the ‘real’ world, and to conceal the fact that real childishness is everywhere.” For Baudrillard, the fiction of Disneyland allows us to think that the real world is just that—real. When, for him it is hyperreal (especially Los Angeles): a series of images and simulacra.

Facebook is not a democracy. However, the use of Facebook, even when acknowledging that it is an autocracy, allows users to believe that democracy is real outside of Facebook. The ubiquity of the site—the fact that so many people use it—make it seem as if it is the perfect vehicle to enact democracy, even if it isn’t one itself. However, this ubiquity feeds the notion that enacting democracy can be as simple as posting a link or a status or a profile picture. “I’m communicating with so many people,” seems to be the thought, “of course this will make a difference.” Posting on the internet, without any real-world action, is lazy activism. It is akin to wearing a sandwich board on the sidewalk, shouting through a megaphone.

The same day Facebook users were writing outraged posts over the new layout, convicted murderer Troy Davis was put to death in Georgia. The execution was controversial, not just because of the fact that it was an execution, but because many of the witnesses who had testified in the trial had changed or recanted their testimony. Yet, through all the appeals and Supreme Court hearing requests, the verdict remained unchanged.

There was plenty of Facebook traffic regarding the case. Many, many of my Facebook friends posted messages of hope for a stay or a pardon, dismay at the fact that the execution was carried out, and scoldings of the people posting about Facebook while a man who may have been innocent was put to death.

The similarity of the Facebook and Troy Davis posts struck me. In a week, or a month, or a year, who will remember what the old Facebook layout even looked like? Can you remember the layout in 2009? Two days after the changes, I see no posts complaining about the layout, when it seemed to be all anyone talked about on Wednesday. Those so passionately posting about Troy Davis are today posting about their writing, their workdays, their plans for the weekend. There is no mention of injustice. There are no links to websites organizing protests against capital punishment. I am not saying there is no Facebook activity regarding Troy Davis—there are numerous pages and posts—I am saying that the traffic in my circle of friends has very little to do with the case two days after the execution.

This image puts the issues into perspective, but it highlights the limits of Facebook activism (I found this image on Facebook).

Facebook provides the illusion, not necessarily of democracy, but of involvement. You can post, you can have your say, you can feel like you’ve been a part of something. Then you can go back to your own life, back to your minutiae, back to being entertained. When speech is not followed up with action, nothing changes. When nothing changes, the powerful maintain power over the masses—whether it is Mark Zuckerberg, the State of Georgia, or a dictator in the Middle East.

As an Epilogue, I must say that I believe in the power of the Freedom of Speech, and I believe that Facebook (or, say, blogs) can act as a key communication tool to foment change—to act as the spark of activism. But the key to activism is action—which takes work in real life, not just online. I am curious to hear how people go about following up their internet communication with action, especially from those who may be rightfully angry about my dismissal of posts regarding Troy Davis.

Share this:

Comments : 1 Comment »

Tags: activism, Clement Greenberg, contemporary culture, Facebook, hyperreality, Jean Baudrillard, Mark Zuckerberg, postmodernism, Troy Davis, Walter Benjamin

Categories : Culture, News Commentary, Our Postmodern Reality